Day: May 6, 2016

5 tips for women who want to strive in business

Women can transform the boardroom better than men.

While the South African workplace has evolved over the years – with a strong focus on racial and gender equality – plans to empower women to take up leadership positions have made little impact and, still, less than 4% of JSE-listed companies have female CEOs.

This is a global trend with a number of countries now undertaking to make female inclusion, in terms of board representation, compulsory.

Women have proven to be effective leaders, especially when it comes to managing large groups of employees with differing personalities and needs.

Research by COO of Zenger Folkman, Bob Sherwin, which looked into women’s leadership effectiveness found that women outperform their male counterparts invariably when it came to a number of vital workplace competencies, including taking more initiative, displaying higher levels of integrity and honesty and building relationships, to name a few.

This said, it is clear that promoting more women into leadership positions will aid companies achieving sustainable success.

Living examples of the powerful brand of leadership women possess include Carly Fiorina, CEO of Hewlett-Packard; Ellen Sirleaf, the former President of Liberia; Angela Merkel, Chancellor of Germany; and Hillary Clinton, a former first lady and current candidate in the American presidential elections.

As the CEO of a white collar staffing organisation in South Africa, I constantly find myself in male dominated contexts but this has never held me back from working towards my goals.

Reasons why only a few women advance to the C-suite (grouping of chief executives) are often linked to feeling as though they ‘can’t have it all’ and prioritising their family responsibilities over growing their careers.

Many women simply do not believe that they have what it takes to thrive in a senior position. This is a direct result of their socialisation and being told that leadership positions are not necessarily a ‘woman’s job’. Organisational culture therefore plays a pivotal role in shifting the attitudes of female staff.

Contrary to what they may believe, numerous studies have found that women are the better leaders than their male counterparts. Of particular interest, an article by Wits Business School graduates explained that companies with more women board directors outperformed those with the least by 53%.

While women earned approximately 34% less than men in the same jobs in 2015, based on research by the World Bank, female leaders have been found to be more effective when it comes to developing their employees. Harvard Business Review also found that female leaders were rated higher by their peers, bosses and direct reports than their male counterparts.

This may be linked to their leadership traits such as that of compassion which was highlighted as one of the leadership traits that matter most in a recent Pew Research Centre study. 65% of respondents added that they find women to be more compassionate than men.

It comes down to the fact that women are wired differently – this is simple genetics – and this is to our advantage. A number of psychologists have been able to explain it quite well, noting that, when women make decisions, they tend to weigh more variables, consider more options and see a wider array of possible solutions to a problem. Women tend to generalise and synthesise and have a broader, more holistic and more contextual perspective of an issue at hand. Ultimately, this means that women often take a more strategic approach to solving problems and never leave out the ‘big picture’.

A nineteenth-century poet, Matthew Arnold, once said: “If ever the world sees a time when women shall come together purely and simply for the benefit and good of mankind, it will be a power such as the world has never known.” He believed that women can change the world for the better – and so do I.

The female talent pool is growing and is becoming an increasingly important demographic in the country, contributing greatly to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). We are definitely capable of taking hold of our boardrooms and being principal decision makers in both business and the country as a whole.

5 tips for women who want to strive in business:

1. Be confident

Women are hard workers, they need to develop their capability and explore more within their field of work. Women must convey confidence and, when they speak, speak with conviction. It is important that they believe in their leadership skills and not doubt themselves. One also needs to distinguish between confidence and arrogance and not cross that line.

2. Role models and mentors

Young women should enlist mentors and ask for feedback on leadership techniques from their senior management. Seeing women in particular, anywhere in the world, succeeding in an ever increasing number of roles helps inspire young women to raise their expectations for their own futures. An obstacle for many South African women is that, sadly, there is a shortage of female role models in the country and a lack of exposure for those who do exist.

3. Be ambitious and do not be afraid to take risks

Diversity is great for business and, in South Africa, management is now a profession where women are filling a substantial share of positions. Women shouldn’t fear to explore and reach their full potential.

4. Improve your communication skills

As a leader you need to be on the same page as the rest of your team, so it’s always wise to work on your communication skills. This will make you an even better leader.

5. Stand your ground and let your strengths shine

It is imperative that women in leadership maintain their core style, at the same time not being afraid to stand their ground when they know they have to lead the organisation in a certain direction.

Kay Vittee is the CEO of Quest Staffing Solutions, www.quest.co.za.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Insight into international HRM Strategies

Michael Armstrong discusses international HRM strategies with Alan Hosking.

In an increasing global workplace, how do you view international HRM strategies?

International HRM strategies are primarily concerned with resourcing, talent management, performance management, reward management and the management of expatriates. In each of these areas, except that of managing expatriates, the strategy will determine the direction in which the company wants to go, in the light of overall considerations relating to convergence or divergence.

There are, however, a number of HRM practices in which the parent company will play a major part. Workforce planning and talent management for more senior staff may be centralised, as may be resourcing decisions that affect the deployment of staff from the parent company or from other countries (third country nationals). The remuneration of senior staff and expatriates will certainly be centralised. While performance management systems will be administered by subsidiaries, the centre may want to ensure that the processes involved conform to what is regarded as best practice within the organisation and provide the information required for talent management and staffing decisions. An international HR function may also be concerned with encouraging the actions required to promote multicultural working throughout the organisation.

How should one resource an international organisation?

International resourcing strategy is based on workforce planning processes, which assess how many people are needed throughout the multinational company (demand forecasting), set out the sources of people available (supply forecasting) and, in the light of these forecasts, prepare action plans for recruitment, selection or assignment.

Workforce planning may be carried out by the parent company HR function, although it will focus mainly on managers, professional and technical staff throughout the global organisation, and is linked to talent management. Workforce planning for junior staff and operatives is more likely to be carried out by subsidiaries, although the centre may require information on their plans.

Resourcing in an international organisation means making policy decisions on how the staffing requirements of headquarters and the foreign subsidiaries can be met, especially for managers, professionals and technical staff. Sparrow, Scullion and Farndale (2011: 42) emphasised that multinational companies (MNCs): ‘increasingly demand highly skilled, highly flexible, mobile employees who can deliver the required results, sometimes in difficult circumstances’.

On the basis of their research, Paik and Ando (2011: 3006) suggested that: ‘To effectively integrate and co-ordinate activities of foreign affiliates, MNCs need to maintain a higher level of control at headquarters. MNC headquarters want foreign affiliates to act as if they were the headquarters’ agents. In this situation, MNCs are inclined to staff foreign affiliates with managers who understand and appreciate headquarters’ directives.’ However, they also noted that this policy may evolve to rely more on the local ‘host’ country staff, as headquarters learns how better to integrate activities of foreign affiliates to achieve global efficiency. Cumulatively, headquarters will learn more about managing in the host country and local practices, and will build relationships with local suppliers and recruit more local employees.

Whichever orientation exists, an important strategic choice has to be made in staffing subsidiaries in an international firm between employing parent company or home company nationals or a combination of the two. Dowling, Festing and Engle (2008) listed the advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

Additionally, or alternatively, a decision may be made to employ third country nationals (TCNs) in certain posts. These might be easier to obtain than home country nationals and could cost less. But as pointed out by Dowling, Festing and Engle (2008), they might not want to return to their own countries after assignment, the host government may resent hiring of TCNs, and national animosities would have to be considered.

Is there a big difference between international talent management and domestic talent management?

Mellahi and Collings (2010: 143–44) defined international talent management as: “The systematic identification of key positions that differentially contribute to the organisation’s sustainable competitive advantage on a global scale, the development of a talent pool of high-performing incumbents to fill these roles which reflects the global scope of the multinational enterprise, the development of a differentiated human resource architecture to facilitate filling these positions with the best available incumbent and to ensure their continued commitment to the organisation.”

They suggested that enabling high-performing home country nationals to become senior managers improves the performance of an international business because: 1) it is able to respond effectively to the demands of local stakeholders; 2) it is legitimising in the host country; and 3) it provides incentives for retaining and motivating talents.

The conduct of international talent management involves basically the same methods as those used in a domestic setting, namely, a pipeline consisting of processes for:

Talent planning: defining what is meant by talent and establishing how many and what sort of talented people are needed now and in the future.

Talent pool definition: on the basis of talent-planning data deciding what sort of talent pool is required. This would consist of the resources of talent available to an organisation in terms of numbers, competencies and skills. It would include identifying pools of talent that possess the potential to move into a number of roles. This replaces the traditional objective of succession planning with its short-term focus on finding replacements for managers who leave. The talent pool is filled mainly from within the organisation, with additions from outside as required. The pool is not managed rigidly. It can be expanded or contracted as demands for talent change, and new members can be included and existing members removed if they are no longer eligible.

Identifying talent internally: by reference to the definitions of talent pool, using assessments of existing staff to decide who is qualified to be included in the talent pool.

Recruiting talent: bringing in talented people from outside the company to supplement internal talent and become additional members of the talent pool.

Performance management: talent is not fixed and therefore needs to be reviewed regularly though performance management, which also provides information on learning and development needs.

Management development and career planning: a continuous programme of developing the abilities of members of the talent pool and, so far as this is possible, planning their careers.

Assignment or promotion: talent pool members are assigned to positions in headquarters or, as expatriates, in foreign subsidiaries. Alternatively, they may be promoted within headquarters or a subsidiary. Although in a fully formed talent management system the talent pool is considered to be the major source for senior assignments or for promotions, people not actually in the pool may still be eligible. If no one suitable is available in the pool then it may be necessary to recruit externally. Those assigned or promoted will still be included in the talent pool.

The answers in this article are extracts from Armstrong’s Handbook of Strategic Human Resource Management by Michael Armstrong, © 2016, and reproduced with permission from Kogan Page Ltd.

Profile

Michael Armstrong is a former chief examiner of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) in the UK, managing partner of E-Reward and an independent management consultant. He has spent 25 years as an HR practitioner, including 12 as HR Director. He has sold over 500,000 books on the subject of human resource management, and is the author of numerous bestselling HR books, published by Kogan Page.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Don’t let managers hire their own teams

Use the people who have the right skills to do your hiring.

One of the more radical ideas in Laszlo Bock’s Work Rules! Insights from inside Google that will transform how you live and lead, is that you shouldn’t let managers hire their own team. HR needs to control that decision.

Think about that for a moment. In the extreme version, if a manager needs a new team member, HR will say, “Fine, we’ll go out and get them and let you know when we are done.” At Google it wouldn’t go that far; the manager would be involved in the decision. However, it’s the extreme version we need to consider because the watered down “manager closely involved” version is too close to the traditional “manager decides/HR helps” model. The fundamental point is whether the real decision making power rests with the manager or with HR.

Here’s why managers shouldn’t pick their own teams: most managers don’t make good hiring decisions (even though they are convinced they do). Since hiring is a crucial decision, we shouldn’t put it in the hands of someone who isn’t good at it.

If the manager isn’t making the choice, who is? The answer is not so much a “who” as a “what”. There should be an evidence-based process that looks at assessment tests, biodata, reference checks and a series of structured interviews. This is the standard sort of process HR should excel at and, if it doesn’t, it should build the capability.

A compromise position might be to let the HR process narrow down the choice to two or three people, all of whom are good, and then let the manager make the final choice. If all the candidates are equally good, then letting the manager make the choice won’t harm the quality of hire. But what if they are not equally good? Are we willing to have a process that often picks the 2nd or 3rd best player because it makes our manager’s happy to have the choice?

There is a more profound reason not to leave the final choice to the manager. If the manager makes the decision, it increases their power relative to the employee. That may not be a good thing. If the employee is chosen by the company; then their first loyalty is to the company; and the manager is just the person who at the moment helps provide direction. Reduction of status differences is one characteristic of high-involvement organisations and this is one way to reduce the status gap.

Managers, of course, will not like this new model at all. They have two good arguments against it and one bad one. The first good argument is that the HR process may be poor and hence hire the wrong people. That’s a good point, but really it’s just a good argument for investing in effective hiring processes, not an argument that we should default to letting managers make the decision, a mechanism which we know is ineffective. The second good argument is that the manager will be more committed to making the new hire successful if they made the hiring decision. That’s true, but it’s probably not sufficient to justify an ineffective hiring process.

The one bad argument will appear in all kinds of guises but you’ll recognise that underneath the guises is the fact that managers like the power of being able to hire and will say anything to try to keep it. Humans like power, so of course they want it, but that’s not a reason to give it to them.

Given how much managers will object to the new model it will be a tough sell. Saying that, “Google does it,” is a strong point, but won’t’ be sufficient. The best strategy is to go about building a really strong evidence-based hiring process and it will become harder and harder for manager’s to make choices that are contrary to the evidence. Once that process is established, the company is in a position to make the decision as to whether they agree with Google that taking hiring power out of the manager’s hands is a good idea.

Taking hiring power away from managers is a radical idea, but it’s a good one.

David Creelman is CEO of Creelman Research, www.creelmanresearch.com, in Canada. He has co-authored a book about the Uber-isation of work (Lead the Work: Navigating a World Beyond Employment) and helps HR professionals build their skills in analytics and evidence-based thinking into the HR Function.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Engage your talent in the digital workplace

This is the second of two (click here for part 1) key paths to achieving sustainable employee engagement in the digital economy.

Last month, I outlined the first path (Aspiration Focused) as a way to achieve employee engagement in the digital economy. This month, I consider the second path.

PATH II (Effectiveness-focused)

This is gladly embraced by corporate entities that are invigorated with the expectations of the key stakeholders and strive to excel innovatively in producing the delight factors as a distinguishing feature of their organisation’s effectiveness in being a formidable competitor. A cohesive culture that strengthens a diverse multi-generational bond is the gel that glues all individual, team, functional and organisational aspirations for achieving congruent goals.

Priority is given to organisational alignment in gauging performance with KRAs/KPIs being facilitative, but not drowning the actual definition of success which focuses on building a closely knit professional community that is universally geared towards achieving desired objectives through responsible corporate governance. This balances the conventional coveting of rewards and recognition with the enterprising munificence of inter-human connectivity based upon shared values. Consequently, the for-profit architecture of a progressive organisation takes on a soulful garb to buffer against any unforeseen disruptions.

Let’s take a brief look at each of the constituent steps to gain a better appreciation for going down the respective path.

Recruitment and Selection (Culture-Based)

This refers to the unconventional practice of giving top priority to hiring desired talent for being a good cultural fit with the organisation, rather than prowess in a particular function. Such an approach is contingent upon the organisation’s ability to provide high quality and necessary training and development. It is primarily led by the HR/Talent Management function with necessary inputs/facilitation from all the other key stakeholders.

Employee Orientation (Value- Based)

This refers to exposing the inducted employees to all the core aspects that are not only relevant to them, but also, deemed to be of value for future career possibilities, cultural assimilation and professional interactions within the organisation, such as insightful learning about aligned functional areas, meeting distinguished previous employees and socialising with influential power brokers within the organisation. It requires keen participation from all the key stakeholders.

Performance Management (Alignment-Based)

This type of performance management is focused on the congruence between the employee, the assigned role(s) and the work environment. It delves into the psychological makeup of the respective individual while polishing the desired competencies. It is concerned with the underlying personality in addition to the observable person. Consequently, this requires close collaboration of the relevant supervisor(s) with the HR/Talent Management function and an in-house/retained psychologist.

Reward and Recognition (Influence-Based)

This type of Reward and Recognition is focused on the level of positive influence that an employee exercises on all the determinants relating to his/ her career progression, such as peer relationships, supervisor interactions, customer interfaces and networking prowess. It goes beyond the visible confines of the KPIs and can be ascertained by using suitable analytical tools, e.g., 360 feedback, critical incident reports and activity logs.

Dynamic Training and Impactful Development

This refers to modeling the training and development according to the individual needs and moving beyond the mass model application of a yearly schedule. It also liberates the training and development function to explore viable options that are outside the classroom, galvanise personal ownership, promote easy access to the trainee and a more informal nature, such as eLearning, virtual reality, mentor-guided projects and free-time for innovative experimentation.

Distinct Talent Recognition (Initiative-Based)

This refers to appreciating the distinguishing value that each employee enterprisingly demonstrates and creating an overall unrestricted Knowledge, Skill, Behaviour and Competency Map for the whole organisation. It requires astute discernment from the supervisor(s) and is geared towards alleviating the simmering resentments that may arise among peers who see ‘identified’ High-Potentials as a privileged class and resort to differential politics for undermining their status.

Employee Empowerment (Enrichment-Based)

This refers to licensing the employees in taking more real-time decisions that are in congruence with the organisational values. It elevates employees from being loyal abiders to model citizens in the execution of their job responsibilities and creates a rich hybrid of confidence and humility while learning from successes and failures. Such ownership also increases the pool of potential successors to key leadership positions and strengthens the employer brand.

Ebullient Activities (Passion- Based)

This refers to finding the drivers for intrinsic motivation that can provide the jovial anchor for employees to align their interests with the organisation and dismiss any lurking thoughts of attrition. It requires lucid communication and insightful understanding of what galvanizes employees into productive actions, such as office-time allocation for personal projects, participating in social entrepreneurship and adventure retreats with senior management.

Employee Engagement (Purpose-Based)

This type of employee engagement is a hybrid of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and unites the employees under a core set of organisational values. It is both expected and nurtured as a key trait of being a team member. It is characterised by an unflinching focus on providing superior service with a healthy dose of delight factors. Consequently, it is quite common to see grateful customers adding a powerful voice, especially through social media, to marketing initiatives.

Leadership Development (Want-Based)

This type of leadership development focuses on preparing current/future leaders with the qualities that go beyond the requirements of the foreseeable future and have a high probability of being in demand in the long term with respect to the changing business landscape, such as ability to leverage big data to make critical business decisions, ability to integrate different mediums of technology to stay ahead of disruptive innovations, and ability to interface with artificial intelligence as part of the diverse workforce.

Succession Management (Promise-Based)

This type of succession management goes beyond the present hierarchical setup within the organisation and focuses on anticipating what kind of organisation needs to exist beyond the foreseeable future. Such a measure ensures that the potential successors are prepared to take on not only the conventional leadership positions, but also, embrace roles that are either nonexistent or in their infancy at the present moment with high probability of becoming the norm in the long term, such as Chief Innovation Officer, Chief Futurist, Chief Data Officer, Chief Momentum Officer, Chief Integration Officer, Chief Interface Officer, Chief Virtual Reality Officer, Chief Human & Artificial Intelligence Workforce Officer and Chief Internet of Things (IoT) Officer.

Sustainable Employee Engagement (Beyond Horizon)

This refers to ensuring sustainable employee engagement beyond the foreseeable future by institutionalising insightful leadership development and succession management practices that focus on retaining the commitment of desired talent by soliciting their unquenchable zeal and unflinching imagination in achieving seamless and ceaseless innovation. Such an undertaking requires that the humanistic elements are irrevocably combined with the judicious use of technology to ensure ‘peaceful’ coexistence in order to meet unforeseen challenges without trepidation/misgivings regarding the respective alliance.

Both of the aforementioned paths lead to sustainable employee engagement, however, the second path is generally preferable as the more enduring approach for progressive organisations since it provides a stronger impetus for maintaining their competitive edge through a more refined and durable way of leveraging the synergies between luminous foresight, astute decisiveness, coalescing culture, invigorating work environment, unambiguous empowerment, seamless compliance, timely execution, impartial self-reflection and the undeterred resilience to ensure effective remedial measures.

Murad Salman Mirza is a Committed Organisational Architect, Positive Change Driver, Unrepentant Success Addict and a globally published author based in the United Arab Emirates.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Click here for Path I.

Have conscious, constructive collisions

Conscious leadership will build great teams and companies.

Have you ever thought long and hard about the impact that you have on other people?

The word Impact can be defined as “the action of one object coming forcibly into contact with another”. It is synonymous with the word ‘collision’. When your words, sense of being, your energy and image collide with your subordinates, your colleagues or any other person that you come across in whatever leadership role you play, what impact do you have?

It is true that good leaders are self-aware. They make an investment in understanding themselves and the impact they have on others. Not only do they go out of their way to reflect on the good, the bad and the ugly about the core of who they are, they take it a step further and actively find ways to tame or weed out disabling and limiting traits that would hold them back from “colliding” constructively with others. Self-awareness is the catalyst for change and change is the catalyst for self-improvement and development.

When people in leadership roles are self-aware, they tend to be relatively constructive, mature and more accepting of others.

Good leaders are deliberate. They tend to be conscious and intentional in their thoughts and actions. When a deliberate and self-aware leader ‘collides’ with a team or subordinates in behaviour or dialogue they tend not to be oblivious to the impact that they are likely to have on the next person. It is for this reason that, even when good leaders ‘collide’ harshly or roughly with others, they do so fully aware of the impact that they will have and there often is a point to it.

In my two decades of being affiliated with various oganisations ranging from companies that I worked for, church organisations, social organisation and so forth, I have come across people that I regarded as leaders and thus allowed myself to be impacted by them. If I were to narrow the list down to my corporate career, I can think of 22 individuals that at one point or another may have had an impact on my career and thus my life. I wonder how many of them could honestly say they generally were deliberate about the impact that they wanted to have on me and my career. I am reminded of my young mentee who captured this ‘impact’ phenomenon in a rather thought provoking narrative. She dubbed her narrative ‘The Boss’:

“He is a decent human being, although he sometimes forgets and thinks that he is beyond human. He has arguably achieved greatness in his young life by Corporate Standards. He is Intelligent and has a whiff of wisdom about him; I can safely say that he has the ‘X Factor’ that makes him a fierce and competitive force in his pursuit for success and power.

He is indeed a complex individual, I would rather he were just a simple wise guy. He is the leader of our pack – the Chief in charge; he plays different roles as he leads us, although he is not necessarily great at all of them. He has a way of ‘speaking himself and his views’ up into a self-fulfilling prophecy. There are a few peculiarities about him – He thrives on crises and has a way either creating or unearthing crises. He is the epitome of contradictions and paradoxes and yet demands stability and consistency from those around him. He writes people up and down as he pleases; he cuts himself a lot of slack, a courtesy that he never affords anyone else.

He is powerful and knows how to use and abuse it; he is a master at delegating responsibility without empowerment. He is the master puppeteer who does not fully trust anyone but rarely stops to consider if he is trustworthy. He is an amazing orator, who from time to time would inspire his followers beyond imagination but sadly it is through the very same oratory skills that he decapitates and amputates the human soul. He is innocence and manipulation; good and deception; destruction and excellence rolled into one. He destroys what he builds and builds what he destroys. He claims to care but his being does not care.

He is The Boss, He has so much power that it sometimes gets in the way of his humaneness. He makes the lives of many unbearable and of some fulfilling. With his title comes a lot of rights, rights only available to him and a select few. He claims to despise inequality and lack of fairness but breeds and nurtures it in the way he leads. He is fork tongued and has multiple faces – He is The Boss – I would like to meet his soul.”

Leadership is a personal experience both for the leader and the follower; why then do most leaders treat it as a theory or something to be admired in others, nobler than the average human being? As leaders, we touch real people who live real lives. How about we be deliberate about it?

I have heard one too many leaders claim not to have deliberately destroyed a person’s career or life in their political corporate pursuits. I have heard one too many leaders boast about swimming with the sharks and therefore have to ‘eat or be eaten’. I have heard one too many leaders claim that there is a clear line between business interactions and human interactions, which gives one a licence to ‘collide’ anyhow with whoever is around them at a business level – no hard feelings, they say. I say leaders must do what they need to do only with a lot more self-awareness, clear intent and consciousness. Maybe, just maybe, we would have a lot less broken corporate inmates and a lot more fully engaged corporate teammates.

Mpume Makhubela is the CEO of Huvest People Solutions, www.huvest.co.za.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Build your pipeline of women leaders

Failure to build talent pipelines threatens women’s workplace progress.

Women are under-represented in the workforce globally, and if organisations maintain the current rate of progress, female representation will reach only 40% globally in the professional and managerial ranks in 2025, according to Mercer’s second annual When Women Thrive global report.

Among the key trends revealed in the report is that women’s representation within organisations actually declines as career levels rise, from support staff through the executive level. “The traditional methods of advancing women aren’t moving the needle, and under-representation of women around the world has become an economic and social travesty,” says Pat Milligan, Mercer’s Global Leader of When Women Thrive. “While leaders have been focusing on women at the top, they’re largely ignoring the female talent pipelines so critical to maintaining progress.”

“This is a call-to-action, every organisation has a choice to stay with the status quo or drive their growth, communities and economies through the power of women.”

The report finds that, although women are 1.5 times more likely than men to be hired at the executive level, they are also leaving organisations from the highest rank at 1.3 times the rate of men, undermining gains at the top.

According to the When Women Thrive report, women make up 40% of the average company’s workforce. Globally, they represent 33% of managers, 26% of senior managers, and 20% of executives.

“In 10 years, organisations won’t even be close to gender equality in most regions of the world,” said Ms. Milligan. “If CEOs want to drive their growth tomorrow through diversity, they need to take action today.”

The research

The most comprehensive of its kind featuring input from nearly 600 organisations around the world, employing 3.2 million people, including 1.3 million women, identifies a host of key drivers known to improve diversity and inclusion (D and I) efforts.

“It’s not enough to create a band-aid programme,” said Brian Levine, Mercer’s Innovation Leader, and Global Workforce Analytics. “Most companies aren’t focused on the complete talent pipeline nor are they focused on the supporting practices and cultural change critical to ensure that women will be successful in their organisations.”

Only 9% of organisations surveyed globally offer women-focused retirement and savings programmes with the US/Canada ranking first (14%), despite research proving that such efforts lead to greater representation of women.

Other key findings

– Only 57% of organisations claim senior leaders are engaged in diversity and inclusion initiatives with US/Canada ranking #1; – Latin America ranks #1 for engagement of middle managers with 51% vs. 39% globally;

– Involvement of men has actually dropped since the first report in 2014, when 49% of organisations said they are engaged in D and I efforts vs. 38% in 2015. US/Canada ranks #1 for involvement of men at 43%;

• Only 29% of organisations review performance ratings by gender with Australia/New Zealand ranking first;

• US/Canada lead on pay equity, with 40% of organisations offering formal pay equity remediation processes, compared to 34% globally, 25% in Asia, and 28% in Europe. But virtually no improvements have been made since 2014;

• 28% of women hold P&L (profit and loss) roles with Latin America ranking first (47%), followed by Asia (27%), Australia/New Zealand (25%), US/Canada (22%), and Europe (17%);

• Women are perceived to have unique skills needed in today’s market, including flexibility and adaptability (39% vs 20% who say men have those strengths); inclusive team management (43% vs. 20%); and emotional intelligence (24% vs. 5%); and

• About half of organisations in three key regions, Asia, US/Canada and Latin America agree that supporting women’s health is important to attract and retain women, yet only 22% conduct analyses to identify gender-specific health needs in the workforce.

The report also asked organisations about access to and usage of key benefit programmes, including part-time schedules, maternity leave, paternity leave, child care, elder care, mentorship and more.

To access the report summary, click here.

Anne-Magriet Schoeman is the Talent/Country Leader at Mercer Consulting (South Africa) Pty Ltd, www.mercer.com.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Are your working conditions basic, improved or advanced?

When it comes to Conditions of Employment, how are people really treated?

Double standards, paradoxes, contradictions, rhetoric and all sorts of confusing things come the way of HR professionals and make their lives even more complex than they should be. These complexities include human dynamics, labour relations, talent acquisition and legislation. This article discusses and explores a paradox within the South African legislative landscape, that of the Basic Conditions of Employment.

There are quite a few laws, each with their own complexities, merits and peculiarities which govern and regulate the South African workplace in order to ensure that people are treated fairly, that their human rights in the workplace are respected and that the workplace is well organised and disciplined. As a reminder, the purpose of the Basic Conditions of Employment Act, 75 of 1997 as amended, is:

2. The purpose of this Act is to advance economic development and social justice by fulfilling the primary objects of this Act which are—

(a) to give effect to and regulate the right to fair labour practices conferred by section 23(1) of the Constitution—

(i) by establishing and enforcing basic conditions of employment; and

(ii) by regulating the variation of basic conditions of employment;

(b) to give effect to obligations incurred by the Republic as a member state of the International Labour Organisation.

The word “basic” appears twice in the purpose statement and a multitude of times throughout the whole act. This may seem of little relevance and almost insultingly obvious, however herein lies the paradox to be explored.

On a daily basis, we are bombarded and overloaded with a plethora of business related words like “exceed”, “benchmark”, “improve”, “high quality”, “total customer satisfaction”, “our people are our best assets” and “just the very best is good enough”. All of these attempt to create or create the perception that the particular company, product or service is better that any other. Logically speaking, the perpetual drive to improve is necessary for survival, growth and excelling – it simply must happen.

Why is it then that, when it comes to our people, many (it could be most) companies are quite satisfied with “basic” conditions of employment? Why do we rarely hear about business leaders showing off how they have improved the conditions of employment from basic to advanced (or superior)? Is it merely that such good news is not widely communicated? Would we not be experiencing vastly improved job satisfaction, loyalty, customer service satisfaction and overall productivity if we were to provide better conditions of employment?

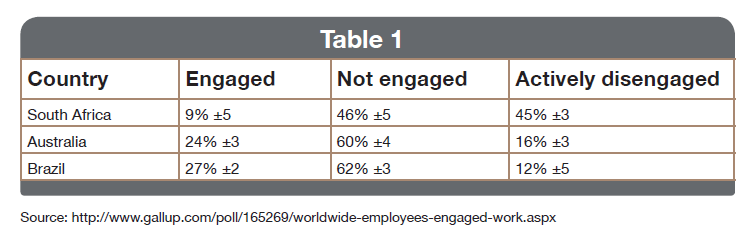

The good news is that there are many companies who do just that and they are, very aptly, referred to as, Employers of Choice, Best Companies To Work For, Top Employers and so forth. Only 13% of employees worldwide are engaged at work, according to Gallup’s new 142-country study on the State of the Global Workplace1. In other words, about one in eight workers — roughly 180 million employees in the countries studied – are psychologically committed to their jobs and likely to be making positive contributions to their organisations. It is quite tempting to think that “these types” of surveys are done in the USA and don’t take the local South African conditions into account. The bad news is that South Africa was one of 142 countries studied and the levels of engagement are low – extremely low – as can be seen from the figures, in Table 1, below.

Could it not be that a possible answer to the question, “Why is it then that, when it comes to our people, many (it could be most) companies are quite satisfied with ‘basic’ conditions of employment?” is that employees are disengaged? In a time where superior service, exceeding minimum standards, excellence, best practice and all the other calls for bragging rights to the best service fill our senses, why is it that when it comes to employees, we do not go beyond basic conditions of employment? Some of the most common reasons have, sadly, become clichés.

“According to Tracy Maylett, CEO of management consulting firm DecisionWise2, employees choose to engage; they can’t be “forced into engagement.” The following passage by Tracy gives a perspective I quite like and ties in nicely with my point.

Being engaged as a manager is not the same as engaging as an employee. The basic forces that drive your personal engagement will be similar to those that drive your team’s engagement, although we are all engaged by different factors and to differing degrees. But an engaged manager is more than simply an engaged employee: There’s a lot more to it.

For many managers, engagement means “getting you to do what I want you to do.” If you comply, you must be engaged. Congratulations! Except that’s wrong. An engaged manager doesn’t coerce by bringing to bear either real or perceived threats of penalty, loss of privilege, termination and so on. Employees choose to engage; they can’t be “forced into engagement.”

The engaged manager is responsible for putting in place the conditions that will empower employees to choose engagement. The engagement “keys” – Meaning, Autonomy, Growth, Impact and Connect (M-A-G-I-C) – are primarily the responsibility of the individual employee. In other words, employees choose to engage because they find meaning (… autonomy, growth, impact, connection) in their work. At the same time, however, the manager is responsible for ensuring the environment is in place that will allow an employee to choose to engage.

Engaged managers till the soil for their direct reports, creating the same conditions that lead to the manager’s full engagement in work and workplace culture. They then encourage employees to find engagement in ways that are unique to them, based on what the manager knows about their passions, interests and needs. Disengaged managers, on the other hand, either don’t know what motivates their people, or simply don’t care. It’s about management by authority, threat and coercion.

There’s a principle in industrial psychology called the Pygmalion effect, which suggests that managerial attitudes, expectations and treatment of employees will explain and predict both behavior and performance. In short, if you as a manager set high expectations for an employee’s performance and communicate those expectations in an affirming way (“I have complete confidence that you can do this”), the employee is likely to perform up to your expectations.

Let me throw another one out there: the Golem effect, named after not the character from The Lord of the Rings but the mythical creature from Jewish folklore. The Golem effect is the opposite of the Pygmalion effect: The negative side of the self-fulfilling prophecy. The disengaged manager expects less from his or her people – or outright expects them to fail – and the team then works at the level of those lower expectations.

A variation on these two effects is the observer-expectancy effect, also called experimenter’s bias. It says that an experimenter or observer – for example, a teacher testing children in a classroom – will often communicate unconscious cues that will cause the subjects to perform in accordance with the observer’s bias. A manager who believes a subordinate incapable of performing well in a given task may unintentionally communicate cues that harm the subordinate’s confidence or otherwise impair her performance. The opposite is also true.

In either case – Pygmalion or Golem – the manager’s expectations often stem directly from his or her level of engagement. If a manager is fully engaged in the workplace, he or she is likely to have a positive view of what the team can do and to communicate that belief in an empowering, encouraging way. Disengaged managers, dissatisfied with the organisation and indifferent about their jobs, “infect” their teams with their apathy, negativity and belief that the work doesn’t matter. The team’s performance reflects it.

So, manager, if your team is disengaged (or engaged!), take a look in the mirror. The correlation isn’t likely due to chance.”

True leaders move beyond basic conditions, they exceed by talking the language of the heart!

Leon Steyn is the Group Human Resources Executive of TMS Group, www.tmsg.co.za.

References

1. http://www.gallup.com/poll/165269/worldwide-employees-engaged-work.aspx

2. http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/246995

This article appeared in May 2016 in the HR Future magazine.

Meet your next generation leaders

How do we motivate the youngest generation in the workplace?

Rewards drive employee morale and have a direct impact on employee performance. With labour costs accounting for more than 50% of the total costs of doing business, it is in an organisation’s best interest to understand their employees better. In fact, it has become an imperative for survival.

In order for organisations to remain competitive and sustainable in the future, they need to understand what motivates the next generational leader. This article summarises the importance of the most well-known motivation theories which we believe are also applicable to the Millennial and next generation leader.

Millennials continue top discussions and baffle organisations with the oldest in the group reaching 35 this year and the youngest 16. They are no longer just entering the workforce but are occupying seats in boardrooms. They hold leadership positions, which are directing or redirecting organisation strategies.

These are our newest board members … how prepared are you for them?

Research has confirmed, and we have experienced it, that they are very refreshing and sometime not so refreshingly different from previous generations and, with that, their expectations and so, too, their total rewards needs and wants.

For decades, research has been trying to answer these five critical questions.

1. Is pay the most important attractor, motivator and retainer for this generation?

2. Will traditional benefit options work for them?

3. As the instant gratification generation – what variable remuneration options will work for them?

4. How should we fulfil their need to be recognised and valued, having been raised by doting parents? and

5. What do they mean and need when it comes to career development?

Some research has gotten it right and others not so right but on the right track. Globalisation has played its part, and changes in technology and push of a button conveniences have opened new worlds of knowledge, opportunity and expectations, not forgetting the South African economy.

The bar keeps shifting and so too their views about work and life as a consequence.

They are a very self-confident, well-educated and technologically advanced generation. They have high expectations for themselves and prefer to work in teams to be safe, rather than as individuals. They don’t want to do boring work and seek challenges and opportunities, yet work life balance is of utmost importance to them. They are looking for work that is meaningful and fulfilling.

So what is it that will excite them to join and stay with organisations?

Our research shows the following:

Pay continues to be an important factor but not the most important factor. Organisational environments are becoming more and more important and organisational culture is topping the charts. They want to be paid well but not at the expense of the right culture fit.

Pay and incentives play an important role in attracting them but not when it comes to motivating, rewarding, and energising and retaining these employees – a lot more is required, it’s not just “about the money”.

The traditional ‘one size fits all’ plans will not suit or work for this generation and they require flexible options giving them flexibility and choice. Cafeteria models may be what is required in the foreseeable future. They grew up with choice, why can they not select their benefits too, they ask. Why must they opt for expensive medical aid plans when they hardly ever get ill and hospital cover is really all they are after.

Reinventing work life balance and flexible work arrangements aimed at enhancing quality of life have universal appeal, this is what they are after. They want the flexibility and to be in control of their own time and feel they have the maturity too.

Recognition is not only a truly basic human need, but has become a necessity for success. This generation craves attention in the forms of feedback and guidance, and appreciate being kept in the loop and seek frequent praise and reassurance. Establish a culture of recognition and feedback.

Are you throwing them into the deep end with the sharks? Are you giving them appropriate career development opportunities? Are you supporting their career aspirations? Does your organisation support their need for educational advancement? Do you have a mentoring and coaching programme in place? Career growth and developmental opportunities is very important for them, more so than pay.

This generation may benefit greatly from mentors who can help guide and develop their young careers. They are not asking for much, just your time and attention.

They want to say what they want to say when they want to say it and not be judged for it.

They are seeking employers who support their aspirations and create opportunities for them to achieve this.

This is the generation who ‘want it all’ and ‘want it now’ in terms of better pay, benefits, rapid career advancement, work/life balance, interesting and challenging work, and making a contribution to society.

What attracts and retains this generation to organisations

Theories of motivation not only endeavour to explain what motivates employees but provides insights into what drives our total reward models. Five of the most influential theories of motivation for Generation Y include the incentive theory of motivation, hierarchy-of-needs, two-factor, expectancy, and equity theory.

Highly motivated employees focus their efforts on achieving specific goals; those who are unmotivated don’t. Paying employees helps, but many other factors influence a person’s desire or lack thereof to excel in the workplace.

Incentive theory of motivation

The incentive theory suggests that people are motivated to do things because of external rewards. For example, you might be motivated to go to work each day for the monetary reward of being paid.

The incentive theory therefore suggests that external rewards is an important consideration for employers and can be seen as the stimulus that attracts a person towards it. Monetary and non-monetary incentives should be provided to employees to motivate them in their work and aids in the attraction and retention of employees.

Maslow’s hierarchy-of-needs theory

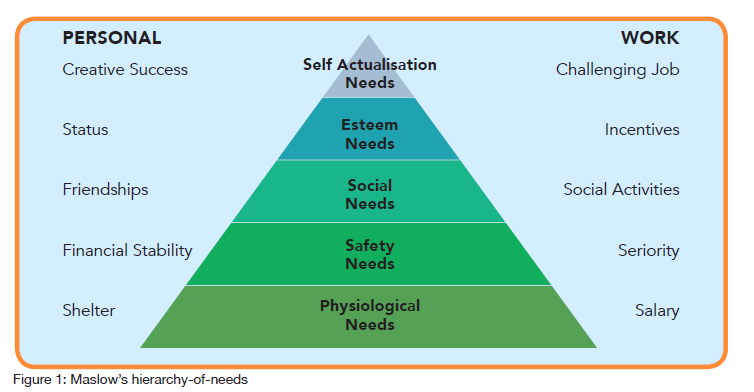

Psychologist Abraham Maslow’s, hierarchy-of-needs theory proposed that we are motivated by the five unmet needs, arranged in the hierarchical order shown in the diagram below. At the bottom are physiological needs, such life-sustaining needs as food and shelter. Working up the hierarchy, we experience safety needs, financial stability, freedom from physical harm, social needs, the need to belong and have friends, esteem needs, the need for self-respect and status, and self-actualisation needs, the need to reach one’s full potential or achieve some creative success.

Employees are motivated by different factors. For some, the ability to have fun at work is a priority and not all employees are driven by the same needs and the needs that motivate individuals can change over time. It is therefore important for organisations to consider which needs different employees are trying to satisfy and should structure rewards and other forms of recognition accordingly.

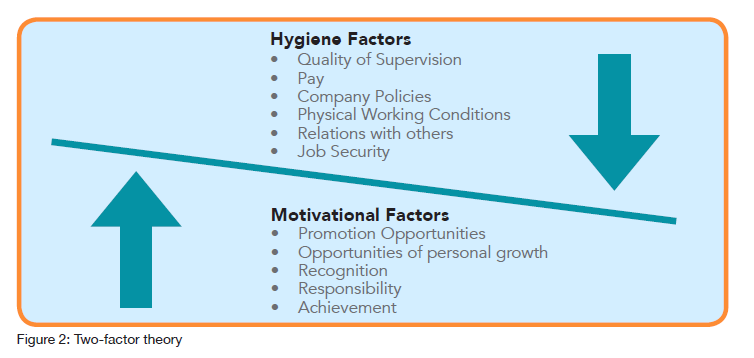

Herzberg’s two-factor theory

Frederick Herzberg, set out to determine which external work factors such as remuneration, job security, or advancement made people feel good about their jobs and which factors made them feel bad about their jobs. He surveyed workers, analysed the results, and concluded that to understand employee satisfaction or dissatisfaction, he had to divide work factors into two categories namely motivation and hygiene.

Motivation factors, those factors that are strong contributors to job satisfaction; and hygiene factors, those factors that are not strong contributors to satisfaction but that must be present to meet a worker’s expectations and prevent job dissatisfaction.

Fixing problems related to hygiene factors may alleviate job dissatisfaction, but it won’t necessarily improve job satisfaction. To increase satisfaction and motivate employees to perform better, organisations must address motivation factors. These include a sense of achievement, recognition, responsibility, opportunity for growth, and meaningfulness of work.

According to Herzberg, motivation requires a two fold approach, eliminating dissatisfies and enhancing satisfiers. Organisation need to understand the importance of blending the employee attitude and workplace motivation.

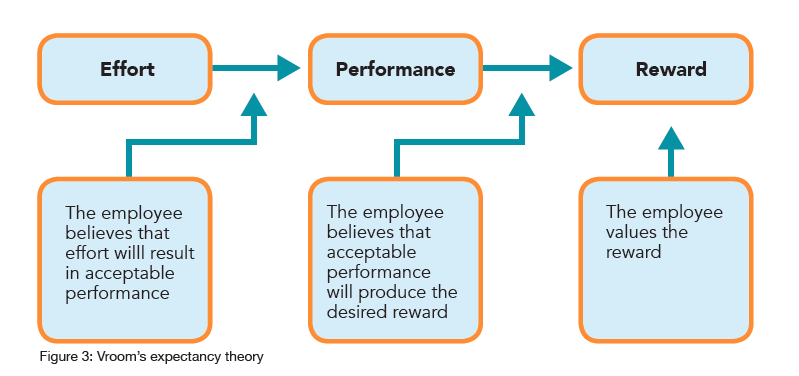

Expectancy theory

Victor Vroom, in his expectancy theory proposes that employees will work hard to earn rewards that they value and that they consider obtainable. He argues that an employee will be motivated to exert a high level of effort to obtain a reward under three conditions:

1. The employee believes that his or her efforts will result in acceptable performance;

2. The employee believes that acceptable performance will lead to the desired outcome or reward; and

3. The employee values the reward.

The expectancy theory proposes that employees work hard to obtain a reward when they value the reward, believe that their efforts will result in acceptable performance, and believe that acceptable performance will lead to a desired outcome or reward.

Equity theory

The equity theory focuses on our perceptions of how fairly we’re treated relative to others. This theory proposes that employees create contributions, rewards ratios that they compare to those of others. If they feel that their ratios are comparable to those of others, they’ll perceive that they’re being treated equitably.

The equity theory is an important factor for this generation and the perception of the rewards received relevant to others. These theories provide an overview of what motivators influence and drives employee’s decision making.

As the war for talent intensifies and competition between organisations increases, it is vital for companies to create a competitive advantage. A total rewards system defines the reward framework for an organisation and their strategy to attract and retain talent. Total rewards is an integral element of reward management and is the combination of financial and non-financial rewards given to employees in exchange for their efforts. It should be perceived as fair.

Dr Mark Bussin is the Executive Chairperson at 21st Century Pay Solutions Group, a Professor at University of Johannesburg, Professor Extraordinaire at North West University, Chairperson and member of various boards and remuneration committees, immediate past President and EXCO member of SARA, and a former Commissioner in the Office of the Presidency. Keshia Mohamed-Padayachee is a Doctoral student.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

How to achieve outcomes from a coaching culture

Creating the companies of tomorrow.

In our previous articles we have described the steps to creating a coaching culture, and considered the crucial first point, defining and aligning the strategy with the organisational strategy. This month we look at the outcomes you can realise through a systematic, systemic integration of coaching as the dominant culture in your organisation.

The model, on the next page, charts the most common developmental stages of a coaching provision and approach, and then links the outputs and outcomes that each stage creates. This demonstrates how organisations which focus only on the supply side of their coaching endeavours, such as having a panel of external coaches or creating a cadre of trained internal coaches, are unlikely to realise the real potential that coaching can produce for their organisation.

Steps 1 and 2: Harvest the learning from coaching conversations

Once an organisation has built its community of external and internal coaches, who understand how coaching contributes to organisational learning and are committed to supporting this, we then assist in harvesting the learning that comes from the many coaching conversations that are taking place.

Firstly, we ensure that coaching relationships start with three-way contracting; the coach, the coachee and someone more senior to the coachee who represents the organisational client, and takes responsibility for how the organisation will benefit and learn through this coaching relationship. A solid three-way contract will detail the company’s objectives for the coaching with clearly defined measures for achievement of these, together with the roles and responsibilities of each party in ensuring their part of a successful outcome, and an explanation of how appropriate confidentiality will be implemented.

This is a delicate balance, as appropriate confidentiality will both support the safety of the coachee in being open and honest with the coach, and at the same time provide for the organisation to learn and benefit from the conversations taking place. Often the coaching process will involve a review meeting midway through the coaching process and a final review at the end, which is attended by all three participants to the contract.

One can assist the harvesting of collective organisational learning by:

– Bringing together at regular intervals the community of internal and external coaches with senior leadership or HR, to hear about the challenges the organisation is experiencing and discuss how coaching can align with other solutions being implemented. This is also a forum for questions about the organisation’s people, culture and development;

– Facilitating supervision for both external and internal coaches, with managed confidentiality; and

– Facilitating dialogue with senior executives and coaches on emerging key themes and how coaching can contribute more to the next stages of the organisation’s development.

This process requires facilitation from a consultant who is not only an experienced coach and skilled coaching supervisor, but also one who understands organisational strategy, culture change, systemic dynamics and organisational development. Most importantly, this facilitator needs to translate between the language of senior leadership and the language of the coaching conversations. There is a shortage of people at this highly skilled level, who can connect the strategic with the personal, commercial and value-based domains within organisations.

Maximising the ROI

In this tough economic environment, it is inevitable that every line of cost will be reviewed. There will be increasing pressure for coaching to demonstrate its return on investment and increase its capacity to develop leaders effectively in a way that makes financial sense, and simultaneously be part of effectively developing the organisation to better succeed in this volatile and fast-changing world.

Professor Peter Hawkins is a business leader, international consultant and Non-Executive Director of Metaco, www.metaco.co.za. He is an acknowledged thought leader in the fields of Leadership, Board and Leadership Development, Coaching, Systemic Team Coaching and Culture Change, a best-selling author in these topics, and an international conference key note speaker. Barbara Walsh is a Principal Consultant, Executive and Leadership Team Coach and Executive Director of Metaco, www.metaco.co.za. She works with senior leadership, leadership teams and HR to achieve far-reaching organisational results. She has an MSc in Coaching and Behavioural Change and is an accredited Neuro-Semantics Coach and Coaching Trainer.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Here are some more technology trends facing HR solutions

The HR solution should be available for use by all in the organisation.

When reviewing a possible new HR solution, the following trends are as follows:

Vendor provided middleware

HR practitioners and their staff are generally not technologists, so the existence of middleware should be, and generally is, an invisible layer of software that is required to integrate the HR solution it is delivered with to other systems and/or technologies already in place within the organisation.

Most if not all HR solution providers would have incorporated middleware and its associated toolsets as part of their delivered solution. As more and more Cloud-based solutions arrive in the market place, the need for integration between solutions provided by different vendors is becoming a more important issue to address. It is therefore imperative that the HR solution you select to implement is delivered with the relevant toolsets to enable integration to your existing systems.

One of the primary causes on this need for middleware is that there has certainly been an increase in the number of organisations implementing a replacement strategy with regards to their current outdated HR solutions, and with this a move to Cloud-based solutions.

In essence, any new vendor entering the HRIS space now has to gracefully coexist with all the other offerings already out there. In the past, when systems were strictly controlled by the IT department, this was their problem to manage, as the HR team were not particularly interested in how the technology was pieced together. All they wanted was a system to log into in the morning, and to be able to get their job done!

With Cloud-based solutions now becoming the predominant delivery model, this problem has moved to becoming the problem of the solution provider, and to address this issue, solution providers have developed a set of middleware to assist in integrating their solution with those already in play within the organisation.

Social media is everywhere

So much has been, and will continue to be, written about the impact of social media. Not only within HR but about the impact it can have on an organisation as a whole. No longer is a complaint letter or email just sent to some unmonitored or unknown recipient. Today, any person who has a complaint, valid or not, with regards to bad service or an inferior product sold to them, literally has the whole world as their audience. And, of course, once it’s out there, it’s impossible to retract, whether the organisation is “guilty” or not.

So organisations need to take cognisance of social media, not only as a threat but also around all of the opportunities that it can provide. And so too should the HR team, as social tools have already disrupted and infiltrated just about every major HR process, whether you’re talking about recruiting, training, on-boarding, employee communications, and even performance management and recognition.

All the leading HR software platforms have in fact now incorporated social tools within their solutions sets, and you should expect this kind of functionality in any solution you choose to implement.

With social media platforms being “live” 24/7, organisations have to accept that they exist in an online social world and, as such, the organisation needs to adapt their thought processes around employee communication and interaction. Employees want to read and learn from their executives, real-time, and they also want to be able to share their thoughts and ideas and be able to communicate these in an online environment.

Essentially, integration into the various social media platforms has moved from being a “nice to have” set of functionality, to now being a “must have” within any provided HR solution.

In summary, the user base for HR solutions has increased a hundred fold and more. No longer is the HR solution the exclusive domain of a few users within the organisation. Today, the functionality provided by the HR solution is used by managers, employees, applicants and even part-time contractors. In essence, every person associated with the organisation is a potential user of the system, and as such, the solution needs to provide for a wide range of needs, while continuing to expand in the functionality it is able to provide.

Rob Bothma is an HR Systems Industry Specialist at NGA Africa, a Fellow of the Institute of People Management (IPM) and past non-executive director and Vice President of the IPM, co-author of the 4th Edition of Contemporary Issues in HRM and member of the Executive Board for HR Pulse.

References:

Josh Bersin – Bersin by Deloitte – www.bersin.com.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

To view the first article in this series, click here.

For the second article in this series, click here.

What can we learn from Nkandla?

Ethical leadership versus Nkandla negative role models and sycophantic followers.

To the extent that we can learn from what’s wrong and unethical as much as we can from what’s good (and sometimes more), the ethical lessons arising from the Nkandla saga deserve our attention.

The negative role model that President Zuma provided by disregarding the legally binding instructions of the Public Protector as regards non-security improvement to Nkandla has damaged the moral fibre of our country. And this damage is made even more severe by the President’s long-standing attempts to undermine the Public Protector and her report, Secure in Comfort.

What this incident highlights is that when faced with a conflict between the law and personal interest, the President chose personal interest. Compliance with the law is a fundamental facet of ethics. That compliance is only going to follow after a court order (the Constitutional Court judgement of 31 March) presents a poor example as regards commitment to the law and to ethical conduct. The message this sends to South Africans, our trade partners and potential investors adds to the negative impact.

A pertinent question that stems from this situation is: how will leaders correct this message in their workplaces and in communities when it stems from the behaviour of the first citizen? The example to be countered is a serious one: the Constitutional Court’s judgement found that “the President thus failed to uphold, defend and respect the Constitution as the supreme law of the land”.

Many people will still strive to do the right thing and to grow and promote ethics despite such a negative verdict. For many others, though, the high-profile nature of the saga involving the President risks fuelling the slippery slope of non-compliance. The potential outcome is not only wider-spread fraud and corruption. We need to recognise that it can also fuel a broad-based disregard for the law, whether that be for traffic regulations or in the form of petty crime.

The Nkandla incident has a further negative element that warrants being examined, namely that so many senior Ministers supported the President throughout his extended campaign to secure his personal comfort. There are situations where such support could arise from the difficult situation when unethical behaviour is an instruction from a superior.

But, for these senior Ministers, was this an instruction or was it a choice? Does protecting their jobs justify not only turning a blind eye to unethical conduct, but also actively supporting such behaviour? Did their fear about the stability of their positions and status impact their commitment to ethics? Did they choose to forget that a better, stronger example is expected of those few who are elected to such high office and carry the responsibility for running our country? The answer echoes the core problem associated with Nkandla – that the pursuit of the benefits of being a favoured colleague was their primary driver.

The added negative consequence of such support was well articulated by political analyst Aubrey Matshiqi, who was quoted as saying that, “It is very clear that the integrity of our democratic institution is being sacrificed on the altar of sycophancy in defence of interest that has very little to do with enhancing the democratic dispensation.”

On the issue of accountability, a cornerstone of sound ethics and a bastion against misconduct, Parliament itself has been called into question. As aptly stated by Professor Pierre de Vos, the Claude Leon Foundation Chair in Constitutional Governance at UCT, in a News24 report: “Parliament doesn’t have a good understanding of its role to hold the executive accountable. Some of it might have to do with their ignorance, some to do with MPs’ insecurities because their positions are dependent on the very same President they have to hold accountable.”

The negative ethical lessons are very clear. The extent to which such negativity has permeated our society is evident in the annual stats from Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. The 2015 global survey of perceived public sector corruption scored South Africa only 44 out of 100, in other words solidly in the lower, less ethical half of the scale. (And this score has been pretty constant over the last few years: 2012 = 43/100; 2013 = 42/100 and 2014 = 44/100.)

But what can be done going forward?

An important start is for ordinary individuals to insist on ethical leadership in all the areas where they work, live and socialise. We should only give our support to those leaders who work for the betterment of their followers – not to the leaders who are more focused on their own welfare.

Another good place to start would be the implementation of the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030. Chapter 14 of the NDP 2030 specifically addresses fighting corruption. This was intended to be acted upon, not become a theoretical publication that just collects dust.

In the same vein, the office of the Public Protector, as a key Chapter Nine institution that performs a critical function in protecting and supporting democracy and upholding ethics in South Africa, needs support. This is especially relevant since Thuli Madonsela ends her term of office on 19 October 2016. Corruption Watch have launched a noteworthy public awareness and mobilisation campaign, Bua Mzansi, to this end.

Finally, as always, it requires that we all strive to be ethical role models and ethics advocates in all the forums in which we exert influence.

Cynthia Schoeman is the MD of Ethics Monitoring and Management Services (Pty) Ltd, www.ethicsmonitor.co.za, and the author of Ethics Can (2014) and Ethics: Giving a Damn, Making a Difference (2012).

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Dress for success in the boardroom

Improve your confidence by looking the part in the boardroom, without appearing like you’re trying too hard.

Well known American business tycoon Nelson D. Rockefeller once said, “People who make the right impression make more money than those who don’t.”

Does your day include chairing an important business meeting, addressing a key group of clients or staff members or negotiating a strategic deal? Utilise your image to increase your chances of success in business – it can be the key to your self-confidence, and ultimately determine your success!

Start by aligning your personal brand with the company brand. Consider your business environment and the expectations of your clients. Understand your company’s dress code – the appearance you’re expected to project to your clients and the general public, for example:

Smart (100% smart – professional, well-groomed and stylish);

Smart-casual (70%/30% relaxed smart, casual chic – also known as business wear); or

Casual-smart (70%/30% casual, but stylish).

Chata tip: A casual work dress code for Casual Fridays differs from a casual home dress code. On dress down days, never wear anything that can be deemed unprofessional! So, no tank tops, beach sandals or cropped jeans! Full-length classic jeans with tailored jackets or shirts, and leather loafers or stylish sandals are more appropriate.

Plan your wardrobe accordingly to ensure that you are never over-dressed or under-dressed for the occasion. It should consist of the correct colours, styles and proportions to flatter your figure. Select a good cross-section of the following:

- 50% basics: Essential items in neutral colours that don’t date easily, like a tailored black jacket and classic white shirt;

- 30% fashionable basics: Fashionable items for a particular season in warm, cool or neutral colours, like an animal print blouse or burgundy trench coat; and

- 20% fashion items: Items you would wear for a maximum of two to three months, like this season’s suede jacket or tassled accessories. Ensure that you are wearing fashion that flatters!

Chata tip: Don’t be afraid to include your personal style in your professional wardrobe – an interesting accessory or on-trend element of fashion can set you apart from the crowd and make you memorable.

‘Mix-and-Match’ to create versatile outfits. This way your outfit can look totally different from day to day. The trick is to work with a few items in different colours, styles and fabrics that suit your lifestyle and co-ordinate well with one another, to create the maximum number of completely different outfits:

– Select a basic three-piece suit in a neutral colour (black, grey, stone etc.);

– Add one or two softer jackets or cardigans in warm/cool colours;

– Add a couple of shirts, blouses and camisoles in a variety of plains and prints;

– Add two to three pairs of pants, smart jeans or skirts in basic colours; and

– Include approximately five add-ons (like a glamorous evening top, printed skirt or black shift dress).

Complete with appropriate accessories. They add the finishing touch to personalise your outfit, and turn an ordinary outfit into a stylish one. An interesting belt, statement necklace, beautiful scarf or exquisite handbag can transform your outfit, while simply changing your belt, shoes, bag and earrings can take you from your board meeting to a glamourous evening cocktail party. Invest in quality and take care not to over-accessorise – use more accessories when you are wearing a plain outfit, and fewer accessories with a busier outfit.

Finally, project a confident image by understanding the importance of personal grooming. Ensure that your clothes are clean, pressed and in good repair, and pay special attention to your hair, makeup, nails, personal hygiene and the appearance of your stationery and business cards. Do a full-mirror scan before you leave for the office to ensure that you look well put-together.

You are judged by the image you project. Build a wardrobe that really works for you, and invest in your personal success in the boardroom and beyond!

Marlise du Plessis is a Chata Romano Corporate Ambassador and Senior Image Consultant, www.chataromano.com.

This article appeared in the May 2016 issue of HR Future magazine.

Use technology to engage Millennials

Companies that embrace technology will gain an advantage when it comes to retaining good talent.

We’re living in a time of radical innovation where old business models and processes are being replaced in a rapid way brought about by technology. Over the past 10 years, we’ve been challenged by a host of technological products and services that have changed the way we communicate, consume, travel and learn. The modern workforce is experiencing these changes first hand with organisations having to deal with an always connected, real time employee base that demands a different way of engaging with their employers and what the bigger meaning is for them where they spend eight hours a day. The on-demand workforce is growing and breaking down traditional employment paradigms. Zappos’ Holacracy approach to management is experimenting with entirely new organisational structures and remote working is becoming a requirement, while employee engagement remains essential.